Hip Hop is 50: A Profile - Roots Manuva

- SQUISH

- Sep 16, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Oct 30, 2023

“Making music is my obsession,” says 51-year-old rap legend Roots Manuva (real name Rodney Smith). “It is a compulsion. Art isn’t something I strive for; it is something I am. When I record, I am always striving for the truth. It’s like a natural reflex.”

Over a fabled 30-year career spent powerfully merging the warped basslines of South London’s sound system culture with a constantly probing, almost prophetic (“Don’t seem too keen to write off the third world debt / cause they profit from holding it down” were the famous bars of “Juggle Tings Proper”) way with words, few would argue against Roots succeeding in this aim.

When he rapped about being content with a slice of cheese on toast back on futuristic breakout hit, “Witness (1 Hope)”, Roots nailed the self-depreciative humbleness of the UK’s working classes every bit as powerfully as Pink Floyd referencing the English “hanging on in quiet desperation”. And his influence can be directly traced through to modern artists as diverse as Kae Tempest to Kojey Radical, with solo records like 1999’s Brand New Second Hand and 2001’s Run Come Save Me still among the finest to ever be released by a British emcee.

Yet because the music press tends to frame UK hip hop as something that only truly began with the rise of grime, the foundational cultural contributions of Roots Manuva are so often downplayed. “I understand why it happens,” he agrees, sighing slightly, “but I also try not to look too deep into it. I’d rather make a new song.”

To understand just exactly where this deep compulsion to create comes from, you must return to the 1970s. Raised by first generation Jamaican immigrants in a down-at-heel Stockwell, some of Roots’ formative memories are of walking past the skatepark on the edge of Brixton, smelling wafting skunk fumes and hearing head nodding tunes coming out of the local Rastafarians’ boomboxes. “From backyards to front gardens, everyone was setting up sound systems,” recalls Roots. “Bass-heavy, Black music is what united the whole community.

This energy was infectious, and these experiences showed a working-class lad how sound could move the people. The artist also recalls watching his preacher father give rabble-raising sermons at the local church: “I guess my dad was rapping in his own kind of way. Watching him [do bible readings] was an early influence for sure. Music became my church.” When hip hop took off in the mainstream in the 1980s, artists like KRS-One and Rakim left an awfully deep impression, with Roots learning more about the human condition from their raps than half a dozen schoolbooks.

Although he started out playing the violin as a 7-year-old (quitting once he realised it wasn’t the best instrument to replicate reggae tunes) and his parents subsequently wanted their son to become a classically trained musician, it was rapping that would turn into Roots’ primary focus. “I paid my dues in community studios / late night sessions, I refined my flows” the artist rapped on “Bashment Boogie”, giving a unique insight into how much he practiced his craft in those early days. Reflecting on what ultimately made him choose to be a rapper, Roots explains today: “I wanted to encompass, and be part of, that anti-establishment spirit.”

Emerging in the early 1990s when UK emcees still awkwardly rapped in American accents, Roots

Manuva - who mixed unruly Caribbean slang with an inherently salt-of-the-earth, South London

sensibility - almost instantly felt like a breath of fresh air. “I hold the eye of the tiger / I’m a natural

improviser” he gruffly rapped on one of his first official appearances as a guest on Blak Twang’s “Queens Head”, coming across like a true British eccentric and someone making a spiritual

breakthrough after smoking a joint filled with old school Cheese.

He cemented this eternally wise energy on 1999 debut, Brand New Second Hand; a sobering rap record that cut through the fallacy of the champagne socialism that defined so much of the Tony Blair years. Filled with regal violin samples and dusty boom bap drums, Roots successfully merged the raw sound of New York hip hop with the grassroots, dub-heavy rave music of Stockwell; locating diamonds in the space inbetween. Whether threatening to slap the bacon out of a crooked cop’s mouth (“Movements”), or referring to his UK rap peers as “riff raff” (“Clockwork”), every lyric felt like an instant quotable. And, to paraphrase Roots himself on the water-rippling, bass-heavy album highlight “Dem Phonies”, this debut quenched the thirst of rap fans desperate to hear from the perspective of a Cockney whose third eye was wide open.

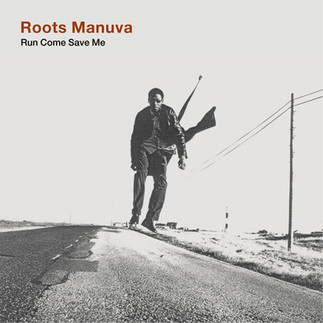

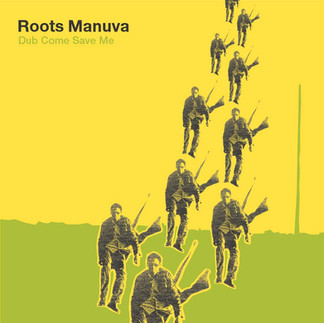

If Brand New Second Hand turned Roots Manuva into a folk hero for UK rap’s underground, it was

its 2001 follow-up that cemented him as a mainstream star. Run Come Save Me featured massive singles “Witness (1 Hope)” and “Dreamy Days”, was nominated for the Mercury Music Prize, and became that rare

UK rap record that the Americans weren’t ashamed to hype up. Filled with ominous flows, fidgety, intergalactic synths, and withering yet hilarious bars (Roots referred to himself as a “fully qualified loon / shaking a fist at the moon” on the deliciously dark “Ital Visions”), the artist consistently came across like a true original. While his rap peers longed for mansions in their bars, Roots rapped about his council flat being a castle and tearing down the Ritz hotel “brick by brick”. With studio album number two, he rubber stamped himself as the voice of the voiceless.

Beyond all the chantable songs, the artist says this particular project had just as much in common with the chest-clearing ideals of blues music. “I always liked how the old blues musicians made their pain sound so pleasant,” explains Roots. “There’s so much weeping and wallowing. You can heart hat same pain in a song like “Dreamy Days” — instinctively, I was doing something similar.”

The prolific output progressed well into the 2000s. On 2005’s Awfully Deep, Roots continued to speak up for those with nothing in his pockets (“I don’t have much nice to say / when day after day there are bills to pay”) and directly channeled the energy of the Windrush Generation with the Caribbean-fuelled vibrancy of “A Haunting”. However, while Awfully Deep solidified Roots Manuva as one of Britain’s most exciting, crossover artists, it’s fair to say that fame was sometimes an uncomfortable fit. And, rather than become the face of endless brand endorsement deals, Roots often chose to withdraw from the glare and instead become a hermit in the studio.

With 2008’s Slime and Reason, and the subsequent Slime and Version, Roots let nostalgia takeover via a series of block party grooves. Its highlight “New Dub” used a crying melodica to reflect the artist’s bluesy grounding. For 2012’s criminally underrated 4everevolution, Roots proved his tongue was sharper than ever, and so many of this project’s ideas (“Skid Valley” talks about the cost of living crisis; the soulful “Much Too Plush” is all about the need to be more frugal) could be talking about the impoverished Britain we all see today; another sign of Roots’ natural foresight.

Although his vocals sounded more withered, 2015’s Bleeds felt like a seasoned veteran reporting back from the frontline to share everything he had learned, with these lessons ranging from the

philosophical idea of having to “overstand to understand” (“Crying”) to the fear that surveillance culture was hitting problematic new lows (“I Know Your Face”). Reflecting on this period of releases, Roots says: “[After the first three records] my focus was being the essence of undefinable. I knew I had to keep pushing, keep changing, and keep mutating with my sound. Those records [Slime and Version onwards] were about smashing through expectations and trying something new.”

Back in 2018, Roots Manuva suffered a serious brain injury (a subdural haematoma), which resulted in him being hospitalised for six months. It resulted in memory loss and a decline in mobility in his left leg, and many still don’t realise that one of the UK’s most innovative artists was so close to losing their life. As someone raised not to make too much of a fuss (something that arguably stopped Roots Manuva from becoming a much bigger star), it was a battle he kept private, until the artist finally put out a statement in 2021 after peers were left confused as to why he had turned down so much work.

The sessions for the heartfelt Bleeds were the kind where no stone was left unturned,

with this exhaustive process likely to have contributed to this health outcome.

However, rather than let this traumatic event derail his artistry, Roots has bravely returned to making music. A knockout guest verse on K*ner’s 2023 single “Do What I Wanna Do” referenced “concrete cotton fields” and the gentrification that has turned Roots’ hometown of Stockwell into the homebase for flat-white drinking yuppies. Just like he’s always done, the artist recognises the power of examining the shortfalls of capitalism.

Some of Roots’ very best work can also be found on 2021 single “So Jazzy”, where the artist channeled Miles Davis at his most optimistic for a sumptuous jazz-enthused rap song that was cut from the same cloth as Guru’s Jazzmatazz sessions. This song contains the alluring, romantic instruction of: “Won’t you put me in your MPC and loop me”. And, for Roots, it’s obvious the new

generation sampling his work would be a beautiful tribute.

Despite still being on the road to recovery, Roots says his famously “mystic mindset” in the studio is becoming more and more prominent. “On a personal level, every day is a new day and I am taking things as they come. But when it comes to the music, every tune still feels like the first tune I ever made. I still get that buzz,” he explains. Like so many people entering their 50s, Roots has found himself increasingly reflective and desperate to make sense of his past. Sometimes he even wonders what he might say to his younger self. “I guess I would tell that boy to stay open, stay aware, and always have a thirst for learning.”

Whether the 2020s are a fruitful creative period for Roots Manuva or not, he can look in the mirror and smile at the reflection of someone responsible for such a rich, timeless discography. “Someone that tried sticking his neck out,” Roots concludes, when asked how he would like to be remembered as an artist. “I want them to say that Roots Manuva pushed the envelope.” That’s a certainty.

Written by Thomas Hobbs